Menu

Close

Close

On May 10, 1869, the last spike of the Transcontinental Railroad was ceremonially driven into a polished laurel railroad tie at Promontory Summit, Utah, to commemorate the joining of the rail lines built by the Central Pacific railroad from the west, and the Union Pacific Railroad from the east. The driving of this final golden spike represented a new era in connecting people, moving goods, and igniting America’s progress.

Beginning with the debut of the first American-based steam locomotive in South Carolina in 1830, the country’s railroad system began to create a connected transportation network. By 1850, more than 9,000 miles of track had been laid east of the Missouri River. By 1861, the amount of track in America exceeded 30,000 miles, with 21,000 in the northern states and 9,500 in the southern states. The railroads became a primary economic force and the locations of stations and tracks could determine the fate of a city or town along its route. This led to early attempts to stop investments in railroads, often by the tavern owners, innkeepers, and stagecoach and canal operators, all who feared this new form of transportation would damage their business. The economic benefits and efficiencies of the locomotives, however, soon convinced investors and politicians that the railroad could reshape the country. Those benefits were undeniable. One of the early railroad companies in New York state created a route that reduced a day-long journey through canals to a one-hour train trip. By 1860, the expanded railroad network and improved locomotive technology meant it only took two days to get from New York City to Chicago. Only 30 years earlier, that same train trip would have taken three weeks.

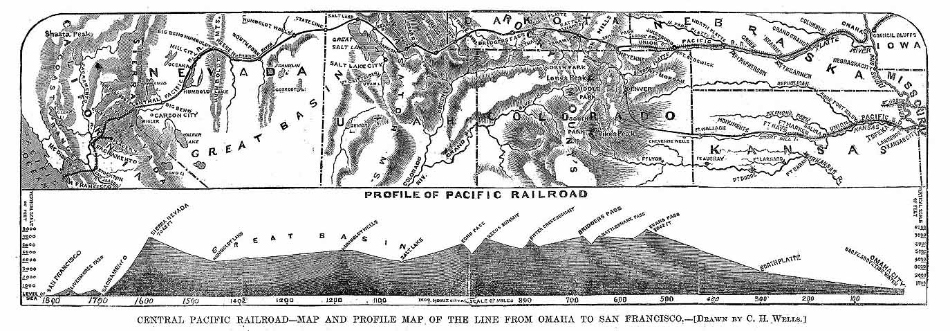

Calls for a railroad that would connect the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the North American continent began in the 1840s, with the first resolution in support of the as-yet undetermined route passing Congress in 1845. It would take 17 years — and the secession of Southern states — to make that initial idea a reality. Few politicians disagreed on the importance of a transcontinental route, especially with the discovery of gold in California in 1849. After all, the only way to reach California from the east was on a six-month boat trip around South America, or shorter but much more dangerous overland trips by horse or wagon. But throughout the 1850s, any attempts to propose funding for the project were stymied by the insistence of Southern states on a route that passed through slave-owning states. In 1860, a young railroad engineer named Theodore Judah proposed a route across the Sierra Nevada mountains that would connect the gold mines of California, the silver mines of Nevada, the settlers in the Oregon territory, and the Mormons in the Great Basin to the rest of the country. Two years later, with the southern states having seceded and no longer blocking the northern route, the proposal became a reality when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act.

The Pacific Railway Act authorized two companies to build the route, and also provided funding as well as land along the route for each mile built. The Union Pacific Railroad started in Omaha, Neb., and worked west, while the Central Pacific Railroad started in Sacramento, Calif., and worked east. Although the Union Pacific did not start building in earnest until the end of the Civil War in 1865, they raced ahead across the flat terrain, at one point laying eight miles of track in one day. Their labor force consisted primarily of Irish workers and Civil War veterans. The greatest danger posed to workers was a constant threat of attacks by Plains Indians — or their fellow workers. As they moved across the plains, temporary encampments would spring near the tracks. These “hell on wheels” camps were crude, dirty, and downright dangerous. The Central Pacific, meanwhile, had to cross the Sierra Nevada mountains. Accomplishing this feat required a labor force of thousands of Chinese workers who used hand tools and explosives and at times could only build one foot of tunnel in a day. The Central Pacific broke through the Sierras in the summer of 1867, and although the Union Pacific had laid four times as much track the Central Pacific began a rapid push across the Great Basin. Both companies were aiming squarely for Ogden in the Utah territory, which they saw as the future crossroads for the west. By 1869, the two companies were within miles of each other and agreed to connect their rails at Promontory Summit. That event happened on May 10, 1869.

Completing the transcontinental railroad had immediate impacts. The formerly isolated West could now be reached by train. Instead of a trip that previously have cost $1,000 or more and took six months, passengers could reach San Francisco from New York City in five days at a cost of $150. It also provided a symbolic unification for a country only four years removed from the Civil War.

Source: Utah History To Go Historians agree that the driving of the golden spike marking the completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, on 10 May 1869 was one of the most important events in United States history, as it was also in Utah history. In fact, 1869 is considered to be a benchmark year in Utah history–the pioneer era coming to an end with the coming of the railroad. Brigham Young, as community leader and president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, foresaw the impact that the coming of the railroad would have and wanted the transcontinental rail line built through Salt Lake City. He was aware of the role that a railroad could play in tying a community together as well as connecting a region with the outside world. After representatives of both the Central Pacific and the Union Pacific met with him and explained the difficulty and extra expense of a route through Salt Lake City, Young accepted the decision and helped wherever he could to speed the completion of the project, including arranging for the use of local contractors for the construction of the tracks across the territory. The construction of a connecting railroad line south to Salt Lake City, and later into almost all parts of the state, had a much larger impact on the local populace than did the joining of the rails at Promontory. In early 1869, prior to the completion of the transcontinental railroad, Mormon Church leaders began working on the organization of a connecting railroad between Ogden and Salt Lake City. In January 1870 that line was completed, connecting Salt Lake City to the national rail system. One of the benefits that the Mormon Church received from the coming of the railroad was the availability of low-cost transportation that would help to bring large numbers of its members to the new Zion. From places as distant as Europe, new members came by way of the ports of call along the East and Gulf coasts. The Union Pacific was the first of the major railroad companies to successfully build within Utah’s borders, connecting with the Central Pacific tracks at Promontory in 1869. Twenty years later, Union Pacific had become the largest railroad company in the territory. In 1889 the Union Pacific consolidated the control of its interests in Utah and Idaho through the organization of the Oregon Short Line and Utah Northern Railway.